Well, it’s happening again – it seems that the financial world is falling apart.

Or so the financial media would have us believe.

Because in recent weeks, we’ve been treated to articles pronouncing the doom of the financial markets, with cherry-picked quotes, apocalyptic prognostications and dire warnings.

Letting In the Fear

And it’s very easy to get swept up in this sentiment.

It’s easy to think the market is going to hell in a handbasket, that this time is different, that it will never recover and all our money will be lost, forever.

It’s easy to fall into this mindset, to let fear in and let it make the investment decisions for you.

Easy – but not very useful.

Is Ignorance Bliss?

Because while the markets could very well implode tomorrow, there’s a lot to be said for simply ignoring the news.

For a few reasons, but mainly because the media will focus on what’s happening right now whereas any investor worth their salt is thinking about the long-term. Meaning that the short-term news is about as useful to an investor as shoes for a gorilla.

As an example, most people reading this will have been invested in the market – in some way or another – for at least 20 years.

Sorry for the Chart

So I think it’s worth taking a look at what’s happened in the market over that period – and compare it to what’s happened in the different ‘short-terms’ that have happened.

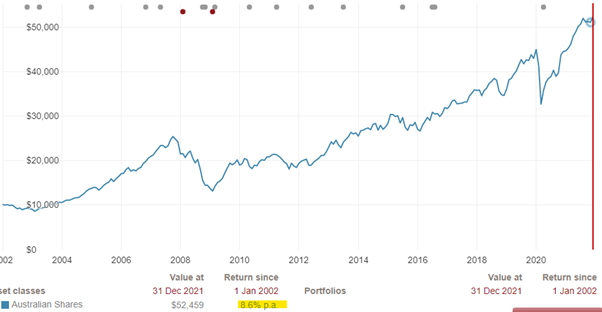

Using the interactive index chart over at Vanguard Investments, we can see how the Australian share market has performed since January 2002:

Now, I tend to avoid throwing this sort of chart around, because, well, they can be pretty dull.

But it’s worth zooming in on the highlighted section on this one – if somebody had put $10,000 into the ‘Australian share market’ (really, a basket of shares reflecting the ASX All Ordinaries accumulation index), reinvested the dividends and otherwise just left it alone, it’d now be worth $52,459.

This works out to an average annual return of 8.6% a year over that period.

But this is the average.

In between there were a lot of decidedly not average periods:

-

For the five-and-a-bit years between January 2002 and November 2007, the average return was a 17.4% a year – a remarkable, and unsustainably high rate.

-

In 2008, the market dropped 40.4% in 12 months. So $10,000 on New Years Day 2008, was worth less than $6,000 on New Years Eve.

-

From January to April 2020, the market fell nearly 21%, taking $10,000 at the start to around $7,900 by Easter.

Finance and Cliché

The financial world loves a cliché, and one of the more useful ones is that:

time IN the market is more important than timING the market.

Meaning that trying to pick the exact best time to get in the market – aiming for December 2001, for instance – is so close to impossible as to be pointless. Instead, you’re better off leaving your money in the market and riding through all of the bumps and slides.

Of course, this is easy to say, but can be hard to do when confronted with your investment dropping in value.

Especially with the media all too ready to tell us when the sky is falling in.

But the thing is, if anybody ever says they know exactly when the market will boom or bust then they’re either deluded, lying, or trying to sell something.

There’s simply no way of knowing, with any certainty, if now is a good, bad or indifferent time to invest in the market. As I write this, there is a chance the market could crash 30% next week – or boom 15%.

I simply have no idea.

Acceptance

Which is a long, and hopefully not worrying, way of saying that if we decide to invest, it’s because we believe it’s better to be invested than not be invested.

And by then making the choice to invest, there are a few realities that we have to continually accept:

-

Markets go up, and they go down.

-

We can never know, with any certainty, which way they’re going to go. Or how fast they’re going to go – or how far they’ll go.

-

Therefore, because we can’t predict the future, we can’t control the future.

-

And if we can’t control it, then we probably shouldn’t worry about it. Too much.

Something to Worry About

Instead of worrying about ‘the market’ (and this applies to any market, be it shares, Australian property, vintage video game consoles, etc), we’re better off focusing on the things we can control – but what are they?

Well, to put it really simply, they’re:

-

Focusing on why we’re investing

Is it because we have extra money each month, is for retirement, or is it for some other, specific goal?

-

Concentrate on how we’re investing

I’ll cover this more in future notes, but how you invest, and how much you’re paying for it, and how you’re managing it on an ongoing basis are all far more important than trying to time one great purchase of an individual winner.

-

Knowing how you’re going to feel as you invest.

Our mindset and emotional reaction to investing is, in some ways, the most significant influence on our eventual returns.

Take, for instance, the completely natural desire to sell everything at the end of 2008, after seeing your money fall by over 40%.

The thing is that by doing so, you’d have missed out on the 26% increase the following year, or the 36% increase by January 2010.

This cycle is at the extreme end but is still entirely natural and very likely to happen again.

So, knowing that, are you going to be nervous the whole time? Is that anxiety an acceptable trade-off for doing what you’ve been told is the ‘right’ thing to do?

Or is it better to take less risk, and accept the lower returns so you can sleep at night?

It’s so important to have this discussion before – and during – your investment ‘journey’.

-

Keeping costs low.

This is a big focus for us when constructing portfolios – decades of research has shown that the average person is probably only going to get the average return of the market, less costs.

So minimising costs should – according to the research – mean you keep more of the returns everyone else is going to get anyway.

No Guarantees

Investing isn’t a sure thing – it’s possible that even with these disciplines, you could still lose money.

(Again, if anybody is ever promising that investing is a sure thing, they’re lying.)

But, if we believe that “it’s better to be invested than not be invested”, then it makes sense to do so as safely as possible, and to increase the likelihood of it working out in your favour – by managing the risks involved.

That’s how we can keep fear out of the decision making process.

Behind the Wheel

“Risk” is something I talk about a lot, but it can really hard to make it seem real before things get bumpy.

So sometimes I use the analogy that investing is like driving.

If we accept that we have to drive, then by doing so we are accepting the risks that come with that (in return for the benefits we want).

Some of those risks we can minimise with good decisions, like wearing a seatbelt, choosing a car with airbags all over the place, staying off our phones while we’re driving.

Some of them we can’t do anything about though – the driver running a red light, the drunk driver sideswiping you, unexpected roadworks throwing out your schedule.

Which is to say, we can mitigate, or reduce, the risks involved in doing something that is, inherently, risky.

But in the end, the price of doing something we want to do – like investing – involves accepting some level of risk.

It’s by following these good habits, though, that we can stay focused on what we want out of our investments – and hopefully, finally, ignore the panic from the media and letting fear dictate our investment strategy.

It empowers somebody to ignore the Chicken Little’s running around saying the sky is about to fall in. It gives us the confidence to hold the course when things are looking dicey.

And it helps us stick to the theory in the moment, rather than let fear wash it all away.

Everything in this post is general information in nature. It’s not meant as financial advice of any kind – be sure to seek personal financial advice before doing anything based on the information in this post.

This is from the first issue of our new newsletter. My aim is to share four things with each, monthly, issue:

-

Something of interest about the financial world for you to read.

-

Notes on how we’ve been helping people lately.

-

An update on things at our end.

-

Something you could share with people that you think they’d benefit from.

If you’re not already subscribed, please feel free to join the list for next month’s issue.